HEADLINE

A renaissance for Cambodia’s glory days of music

"Sin Sisamouth and Ros Serey Sothea, also fell victim. The pair was killed and all their records were destroyed. "

Kannikar Petchkaew

This year marks 40 years on from the genocide in Cambodia, where two million people died from torture, illness, hardship and starvation, when the Khmer Rouge came to power.

Confronting painful history is never easy, but as Kannikar Petchkaew discovered, some Cambodian survivors have found a way to live with the memories.

And to give new life to a once-silenced part of treasured Cambodian culture.

In the early 1970s, a duet by Sin Sisamouth and Ros Serey Sothea ruled the day. The pair are among Cambodia's most beloved singers. Popular and talented, both have recorded more than 100 songs, and each has been a hit.

Sin Sisamouth is widely considered the "King of Khmer music," while the late King Norodom Sihanouk described Ros Serey Sothea as "the golden voice of the royal capital".

Their era became known as the "Golden Age" of Cambodian music.

But, that all changed on April 17, 1975.

When they took control of the country, the Khmer Rouge wiped out all traces of modernity and Western influence.

Intellectuals, artists and musicians were targeted and killed. Sin Sisamouth and Ros Serey Sothea, also fell victim. The pair was killed and all their records were destroyed.

The golden age of Cambodian music was silenced.

The Khmer Rouge’s four-year reign of terror saw two million people killed – a quarter of the entire population.

That’s Youk Chhang, a survivor of the genocide, who is still haunted by that time.

I met him recently in Bangkok.

“I am fifty something now and I’ve never realized peace. My peace definition meaning that one goodnight sleep and you wake up without fear or intimidation and freedom to be with your family and I’ve never had that because I lost all the family inside,” says Chhang.

Khmer Rouge soldiers arrested Youk Chhang when he was 14 – for picking mushrooms to feed his starving, pregnant sister.

He was tortured, while the soldiers killed his sister, aunt, uncle and his grandparents.

Chhang’s family, his mother and siblings, managed to flee across the border to Thailand, where they spent a year in a refugee camp, before eventually making it to the United States before the end of the genocide in 1979.

Seventeen years later Chhang returned to Cambodia as an investigator for the International Genocide Tribunal.

It’s painful to admit, but at first he wanted to see those responsible executed for their crimes.

“I’ve been broken. Society being fragile and I wanted it so much,” he admits.

But after some time he realized that was futile, that executions would not stop the pain.

Instead, he has turned his attention to educating the younger generation.

“I find many means and through my research, people look into academia, look into writing, lecturers, and I think that for young people who don’t have such an experience we need something that is related to them, and that’s music,” says Chhang.

This is how Chhang came up with the idea to reinvigorate Cambodian music, lost under the regime.

Sin Sisamouth, Ros Serey Sothea, and many other musicians from the Cambodian glory days are back.

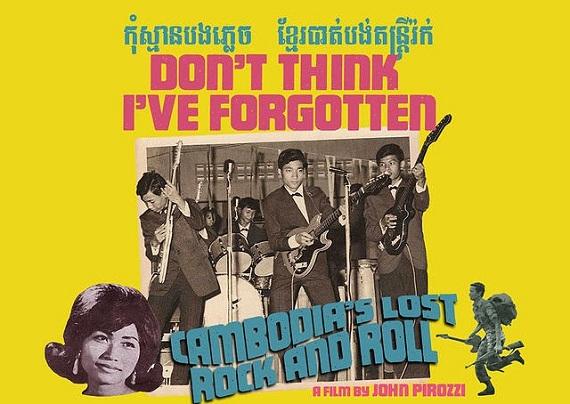

With resources from the Documentation Center of Cambodia, Chhang and his team have produced a film called, “Don’t think I’ve forgotten, the lost Rock and Roll of Cambodia.”

The documentary film tracks the twists and turns of Cambodian music as it morphs into rock and roll, blossoms, and is nearly destroyed along with the rest of the country.

The film is filled with old songs infused with new life through modern techniques.

Chhang says that music has a special way of reaching people, and he hopes the film will help educate young Cambodians about the genocide.

“Genocide is a crime against humanity and music is universal, I think people overlooked the role of artists that have such an influence in the society,” he says, “I saw that they should have their own voice to tell the story and that’s why I chose music.”

The roots of the music run deep in the Cambodian people, he says.

“It’s a sound, it’s a music that goes into their heart and I think it’s in the blood,” he says, “The Khmer Rough killed all artists but because it’s in the blood they can’t. You can’t take away the blood, you can’t.”

The film is yet to be released in theaters but Chhang plans to tour the documentary through every Cambodian village next year.

“It’s a question of preservation, it’s a question of revival, it’s a question of modernism what we are facing now in our culture,” he says, “Without culture we can’t live, if culture dies, then we die.”

- eng

- Kannikar Petchkaew

- Cambodian music

- Khmer Rough

Komentar (0)

KBR percaya pembaca situs ini adalah orang-orang yang cerdas dan terpelajar. Karena itu mari kita gunakan kata-kata yang santun di dalam kolom komentar ini. Kalimat yang sopan, menjauhi prasangka SARA (suku, agama, ras dan antargolongan), pasti akan lebih didengar. Yuk, kita praktikkan!